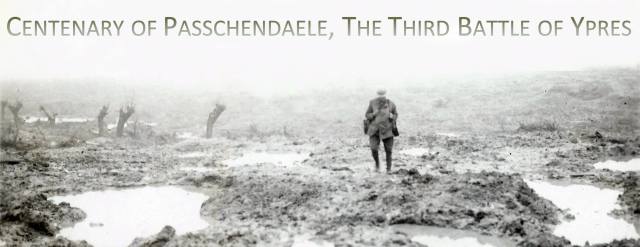

“Our Darkest Hour” – The Centennial Commemorations of the Battle of Passchendaele, Tyne Cot Cemetery, Belgium

For the past 4 years the world has been commemorating the events of World War I (WWI) and New Zealand has been no exception. The Kiwi commemorations began on the 25th of April 2014 at dawn on the beaches of ANZAC cove in Gallipoli, Turkey marking our entrance into world affairs on the global stage as part of the landing force invading the Dardanelles in WWI. The commemorations have continued since then marking all the major events in which New Zealand has taken part. The chance came to participate in the centennial commemorations of the Battle of Passchendaele on the 12th of October 2017, or as we know it “Our Darkest Hour.”

For those of you who do not know or may be asking the question why is this important: The Battle of Passchendaele is particularly poignant for New Zealand and its history. It is often said to be our defining moment when we become a country instead of a colony of the British Empire. The 12th of October is remembered as the darkest hour in our short military history. The day the greatest number of New Zealand soldiers were killed and wounded in a single day. The failed attack on Bellevue Spur left 843 kiwi soldiers dead and some 2 735 wounded in 12 hours, later a further 130 died of their wounds.

Our day began in the car park at the local amusement park beside my hotel where I met up with the cousins. Here we had to clear security checks before boarding buses which would transport us the 7 km to Tyne Cot Cemetery for the commemorations. The security was tight as the services would be attended by HRH Prince William, Duke of Cambridge and HRH Princess Astrid of the Belgians, Arch Duchess of Austria-Este. The commemorations would also be attended by prominent representatives from New Zealand, Britain and Belgium unfortunately the Governor-General elected to pass on attending as she had been here earlier for the commemorations of Messines Ridge. In the party besides the royals, were the NZ ambassador to Belgium Greg Andrews, the Speaker of the NZ Parliament, David Carter, the Chief of our Defence forces Lieutenant-General Tim Keating, VC recipient Willie Apiata and the Mayor of Auckland Phil Goff.

The cemetery

Tyne Cot Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery and Memorial to the Missing is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) burial ground for the dead of the WWI in the Ypres Salient on the Western Front. It is the largest cemetery for Commonwealth forces in the world, for any war. The cemetery and its surrounding memorial are located outside of Passchendaele, near Zonnebeke in Belgium. The name “Tyne Cot” is said to come from the Northumberland Fusiliers, who on seeing a resemblance between the many German concrete pill boxes on this site and the typical Tyneside workers’ cottages (Tyne cots). Tyne Cot Cemetery lies on a broad rise in the landscape which overlooks the surrounding countryside. As such, the location was strategically important to both sides fighting in the area. The concrete shelters which still stand in various parts of the cemetery were part of a fortified position of the German Flandern I Stellung, which played an important tactical role during the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917.

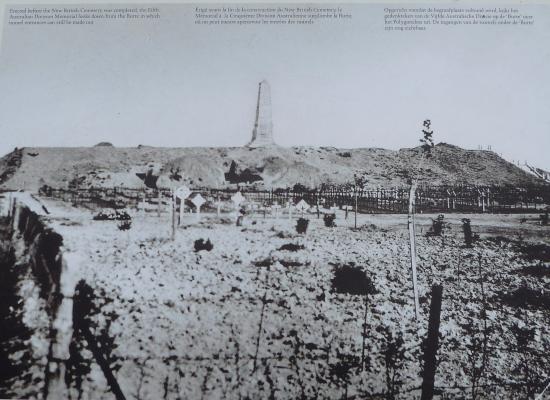

On 4th October 1917, the area where Tyne Cot Cemetery is now located, was captured by the 3rd Australian Division and the New Zealand Division and two days later a cemetery for British and Canadian war dead was begun. The cemetery was recaptured by German forces on the 13th April 1918 and was finally liberated by Belgian forces on the 28th of September 1918.

After the Armistice in November 1918, the cemetery was greatly enlarged from its original 343 graves by concentrating graves from the battlefields and smaller cemeteries nearby. The cemetery grounds were assigned to the United Kingdom in perpetuity by King Albert I of Belgium in recognition of the sacrifices made by the British Empire in the defence and liberation of Belgium during the war.

The Cross of Sacrifice that marks many CWGC cemeteries was built on top of a German pill box in the centre of the cemetery, purportedly at the suggestion of King George V, who visited the cemetery in 1922 as it neared completion. The King’s speech included the following in which he said:

We can truly say that the whole circuit of the Earth is girdled with the graves of our dead. In the course of my pilgrimage, I have many times asked myself whether there can be more potent advocates of peace upon Earth through the years to come, than this massed multitude of silent witnesses to the desolation of war.

— King George V, 11 May 1922

Upon completion of the Menin Gate, builders discovered it was not large enough to contain all the names as originally planned. They selected an arbitrary cut-off date of the 15th August 1917 and the names of the missing after this date were inscribed on the Tyne Cot Memorial instead. The New Zealand contingent of the CWGC declined to have its missing soldiers names listed on the main memorials, choosing instead to have names listed near to the appropriate battles. Tyne Cot was chosen as one of these locations. Unlike the other New Zealand memorials to its missing, the Tyne Cot New Zealand Memorial to the missing is integrated within the larger Tyne Cot Memorial, forming a central apse in the main memorial wall. The inscription reads: “Here are recorded the names of officers and men of New Zealand who fell in the Battle of Broodseinde and the First Battle of Passchendaele October 1917 and whose graves are known only unto God”. The cemetery has 11,965 graves, of which 8,369 are unnamed and the Memorial contains the names of 33,783 soldiers of the UK forces, plus a further 1,176 New Zealanders.

The Battle we commemorate.

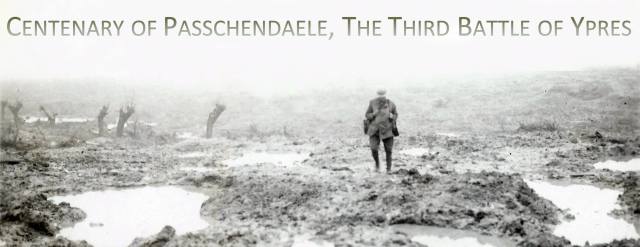

The First Battle of Passchendaele (3rd Battle of Ypres Salient) on the 12th of October was another Allied attempt to gain ground around Passchendaele. Heavy rain and mud again made movement difficult and little artillery could be brought close to the front. Allied troops were exhausted and morale had fallen. After a modest British advance, German counter-attacks recovered most of the ground lost at Passchendaele.

On the 12th of October 1917, it was planned that the 3rd Australian Division would attack Passchendaele ridge and the village, and the New Zealand Division would capture the Bellevue Spur about 13 km outside Ypres. They were to push the Germans back about 2 km to allow the capture of the village of Passchendaele. The New Zealand Division contained two attacking brigades each with a machine-gun company and three other machine-gun companies maintaining a machine-gun barrage. The division had the support of one-hundred and forty-four 18-pounder field guns and forty-eight 4.5 inch howitzers. The artillery was expected to move forward after the final objective was achieved, to bombard German-held ground from positions 1-2 km beyond Passchendaele village.

Plans well laid but the rain had fallen all night long on the 11th & 12th of October saturating the terrain to be attacked and turning it into a bog making movement difficult (the summer/autumn of 1917 had been the wettest in over 30 years). The Germans opposite the New Zealanders had been alert all night, sending up flares and conducting an artillery bombardment (including gas) on the New Zealand front line from 5.00 am which hit the New Zealand trench mortar personnel and destroyed their ammunition. The New Zealand advance was obstructed by uncut barbed wire and German machine-gun pillboxes. The creeping barrage from the field-guns was almost absent as the guns were bogged down while others had been knocked out by German artillery. The creeping barrage diminished as they moved forward and howitzer shells plunging into wet ground around the Bellevue pillboxes, exploded harmlessly because the mud smothered the high-explosive shell-detonations.

The German artillery could fire all the way to the rear of the New Zealand Divisional area and the machine-gun barrages from the German pillboxes raked the advance. They were caught between both. The division gained some ground but was stopped by the constant need to cross barbed wire 20–45 m deep while constantly being raked by machine-gun fire. The British tried an artillery bombardment to support the attack but the shells fell short dropping on some of the New Zealand positions. They were being bombarded not only by the Germans but their own forces as well. By the end of the day the NZ troops were forced to retreat and the area they had taken during the day was lost to the Germans. The resulting carnage had left 843 Kiwi soldiers dead and some 2 735 wounded. In places, the mud was so deep that men who were wounded and fell, sank into the mud and drowned. Medics who tried to retrieve the wounded would often become bogged down up to their waist in mud unable to move.

In March 1918, British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, wrote in his war memoirs that “Passchendaele was indeed one of the greatest disasters of the war […] No soldier of any intelligence now defends this senseless campaign.”

In 1920, the war reporter Philip Gibbs—who had himself witnessed the Third Ypres Battle—wrote that “…nothing that has been written is more than the pale image of the abomination of those battlefields, and that no pen or brush has yet achieved the picture of that Armageddon in which so many of our men perished”.

In 2007, Glyn Harper wrote that “…. more New Zealanders were killed or maimed in these few short hours than on any other day in the nation’s history.”

The Ceremony 100 years later.

The ceremony began at 11 am with the arrival of HRH Prince William and HRH Princess Astrid who were lead through the cemetery by the NZ Defence Force Maori Culture Party to the Central Apse in the Memorial Wall containing the names of the New Zealand dead. A key element which would be a leading theme through the ceremony was to be the Kiwi music and Maori traditions. The original regimental colours of the 4th Otago Southland Battalion from the battle were present.

The Speaker of the New Zealand Parliament, David Carter lead the speeches describing New Zealand in 1914, the dedication of its people, and its entrance into the war on the beaches of Gallipoli, the massive loss of life and the heroism shown there before they were withdrawn and redeployed to the battlefields of France and Belgium. Their subsequent participation in the Battles of Arras, Somme, Messines and Broodseinde leading up to Passchendaele. He would go on to clarified why the Battle of Passchendaele would go on to be known as our “darkest hour”. While the other battles would be remembered for their victories, Passchendaele would always represent a black chapter in our military history by the sheer carnage and loss of NZ live in such a few short hours, and the unbelievable heroism shown by those who survived. He would offer the greetings and thanks our tiny nation to those Kiwis who made the ultimate sacrifice and who never returned to their homeland reminding them that they will never be forgotten.

HRH Prince William followed David Carter highlighting the cost NZ paid in young men’s lives. Almost 60% of the 100,000 New Zealanders who went to war became casualties. More than 18,000 died of wounds or disease — 12,483 of them in France and Belgium. From a population of little more than a million people in 1914, this meant that about one in four New Zealand men between the ages of 20 and 45 was either killed or wounded. Horrific figures for a little nation at the uttermost ends of the earth. He too would also thanks to them from a grateful British nation.

HRH Princess Astrid in her speech would highlight the role NZ women played who gave up their sons, the NZ women in the Medical Core who served and lost their lives and the women of New Zealand who collected and sent food and clothing to save the Belgians from starvation. She referred to her grandmother Queen Elisabeth who had actively visited and worked with the nursing units at the front and her experiences in meeting the Kiwi nurses. She later created the Queen Elisabeth Medal to recognise exceptional services to Belgium in the relief of the suffering of its citizens during the WWI. Many NZ women received the medal. The Princess also reiterated the thanks and gratefulness of the Belgium people to that little nation on the other side of the earth who few had heard of and who had sacrificed so much.

The final speech was given by the Chief of our Defence forces Lieutenant-General Tim Keating. He would touch on the traumas of the battle, not just for the soldiers but also the poor Belgians caught in between. He would highlight the traumas of the NZ commanders and their inability to influence the slaughter. He would mention the ritual guilt they suffered and the re-examination of decision making while trying to influence decisions and battle plans with limited effect. For those who did challenge their superiors were summarily relieved and replaced by those who would carry out the orders without question. Before the disastrous attack of the 12th of October, NZ senior offices were worried about the prospects for the operation. The Commander of the NZ artillery division Brigadier-General Napier Johnston, wrote in his diary on the eve of the 12th of October that: “…the generals could not depend on the artillery tomorrow. I do not feel confident, things are rushed too much, the weather is rotten, the roads are very bad and the objectives have not been properly bombarded.” The day after the disastrous battle and its failure he wrote: “…today has been a bad day for us. My opinion is that the senior Generals who direct these operations are not conversant with the conditions – mud, cold, rain and no shelter for the men, and finally the Germans are not as played out as the make out.” The Commander of the NZ Division, Major-General Sir Andrew Russell had built the NZ division from the shreds of Gallipoli to one of the best Divisions on the Western Front responsible for a large number of the Allied successes. He was well respected by his men but felt the full responsibility for the disaster, and was the only man in the command structure to admit the mistake. It would haunt him for the rest of his life and at times render him an invalid. Today we would call that Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Each speech was followed by well known New Zealand music adding a touch of home and with a tug at the old heart strings adding to the sombre emotions of the moment. When the song “Poppies and Pohutukawa” was sung I don’t think there were many who didn’t shed a tear as the lyrics summed up the feeling for these men who never saw home again. As the remembrance ceremony drew to a close, wreaths were laid by Belgians and New Zealanders alike, the ode was said and the trumpets sounded out the Last Post over the thousands who were laid to rest here and remembered on the walls.

The entire ceremony can be viewed on the NZ Defence force channel on YouTube by clicking on the following link: Passchendaele National Commemoration 12th Oct 2017

A moment for personal dedication & reflection

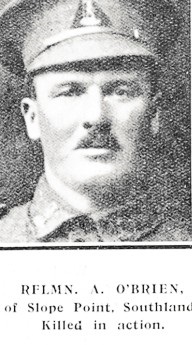

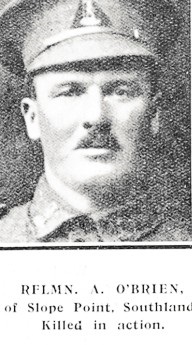

Both my parental and maternal families were not spared these horrors. My paternal (and my cousins too) grandmother had a brother (Tim Flynn) and a cousin (Michael Flynn) who participated in this battle. Her brother returned a broken man and her cousin is missing in action in the fields of Flanders. My mother’s great uncle, Andrew O’Brien also fell on the same day and is also missing in action in the fields of Flanders alongside Michael.

Bronwyn and I were able to visit the NZ Apse in the Memorial Wall to the dead prior to the ceremony where we were able to see Andrew’s and Michael’s names engraved on the wall of remembrance for those who fell but have no known grave. We were able to mark their names with a poppy and remind them they were not forgotten even though they were 18 821 km from home.

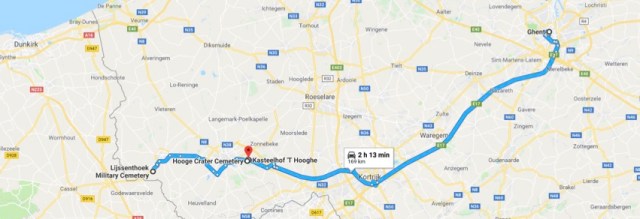

Andrew joined up in October 1915 and arrived in France in March 1916 where he served with the 3rd Battalion NZ Rifle Brigade (known as the Dinks). He had served 2 years on the Western Front and may have been involved in both the Battle of the Somme and Messines Ridge before he died at the Battle of Passchendaele in the area known as Abraham Heights on the 12th of October 1917 aged 35. Michael served with the Otago Infantry Regiment and had barely served 6 months on the Western Front when he was killed on the 17th of October aged 35 also in the area of Abraham Heights. He joined up in September 1916 but in November 1916 contracted Spanish Influenza and almost did not go overseas. He recovered and was shipped out, arriving in France in March 1917. In the battle, the Otago Infantry Regiment took over the advanced positions held by the 3rd Rifle Brigade (Andrew’s brigade) after the Passchendaele attack, extending approximately from the cemetery (white cross on map) up towards Berlin Wood. Michael’s regiment was the one to relieve Andrew’s regiment on the 14th of October.

We acquired some interesting information while at the commemoration. Steve had the luck to sit by a women from Auckland who was actively involved with research into WWI. In friendly conversation, she asked what connections we had to the battle and Michael & Andrew came up. With a few quick flicks on her iPad she had found their records. Unfortunately, there was very little information regarding Andrew but we learned quite a bit more about Michael. He wasn’t just missing in action, he had been found and buried as his records show (see picture), “…grave close by the front line, cross was erected, grave fell into German hands and is now lost..” Michael may well have been buried in the area of the white cross on the map but the cemetery would later be raised at Tyne Cot (see square in bottom picture). He may well be one of the 8,369 unnamed graves in Tyne Cot.

After tending to our own relatives I also added poppies to those names I had on my list from the Gore RSA Roll of Honour. I found the Otago Regiment had been well visited with almost all the names having poppies placed on them and I was able to fill in a few more. There must have been a large contingent visiting from the Otago/Southland area compared to the other areas of NZ and their Regiment panels. As I moved around the panel placing the poppies an English gentleman come up to me and inquired as to my connections with the wall. As the conversation progressed and I told him of Andrew & Michael and the Gore RSA Roll of Honour and I keep thinking, I know your face but just can’t place the name. He expressed a genuine interest in their stories and in the Southern area of NZ which had not visited. Anyway the conversation concluded and he moved on to talk to others who were also tending to the names on the wall. It bugged me that I could not place who he was for the life of me. It was not until the ceremony began and when he was introduced that I realised who he was…Princess Anne’s husband Vice-Admiral Sir Tim Lawrence, deputy chairman of the CWGC! At times my memory for names and faces evades me – early signs of old age?

I also tended to the graves on my list while wandering around the cemetery. The NZ Aspe is just a small colonnade in the long memorial wall. From the top of the Cross of Sacrifice (on top of a German pill box) you obtain magnificent views over the cemetery and surrounding landscape where most of these soldiers fell within not more than a few hundred metres from here. Within the grounds of the cemetery there are at least 3 other German pillboxes.

Time to depart and get some lunch and rest before attending the evening ceremony at Polygon Wood. As I was about to board a buss back to town, a mad little Belgian Policeman began shouting “Royals! Royals! ” and ushered the bus away before we could get on and around the corner of the narrow country lane comes Prince William’s and Princess Astrid’s limos. It was a case of suck in the belly and pull in your feet or something is going to get run over. 🙂